ESG & Sustainability

NELA is putting our commitment to sustainability into action through the work of our new ESG & Sustainability portfolio.

We will be providing regular updates in the form of website publications and seminars.

We encourage you to bookmark this page and follow NELA on social media, to stay up to date with NELA’s work in this space and find information about how you and your organisation can participate.

In 2023 NELA established an ESG and Sustainability Portfolio. NELA believes that ESG encompasses everything we do in living our purpose to be a ‘peak body for advancing environmental law’.

The primary goal for this portfolio is to guide NELA towards becoming a recognised leader in sustainability by analysing, monitoring and regularly reporting on NELA’s ESG impact.

In 2023 we will publish our first self-assessment on our ESG impact. NELA’s purpose is to be ‘a peak body for advancing Australian environmental law’. In promoting a mature systems approach to ESG, we believe looking internally at our own impacts and sustainable improvements is the first step in living our purpose through with an ESG lens.

The subsidiary goal for this portfolio is to identify ways to use NELA’s sustainability impact assessment and monitoring to create educational opportunities for NELA’s members and stakeholders. We will publish articles and hold seminars and presentations across the year to bring a clear-eyed perspective and advocate for advancement of external regulation of ESG and sustainability.

The portfolio will have close working relationships with other NELA work on ESG elements, such as NELA’s Climate and Biodiversity Working Groups.

The portfolio is brought to you by:

- Michelle Brooks – NELA Director and National Convenor (on leave), ESG and Sustainability Portfolio

- Dr Phillipa McCormack – NELA Director and Acting Co-Convenor Convenor, ESG and Sustainability Portfolio

- Reid Thornett – NELA Sustainability Officer, and Acting Co-Convenor, ESG and Sustainability Portfolio

- Sarah Brugler – NELA Director and Sustainability Officer

- Kara Postle – NELA Sustainability Officer

- Matthew Wilkinson-Luck – NELA Sustainability Officer

- Michael Tangonan – NELA Sustainability Officer

If you would like to get involved you can reach us at sustainability@nela.org.au

NELA’s ESG Impact:

Understanding NELA’s impact required our portfolio to undertake an ESG impact assessment of our organisation: a comprehensive evaluation of an our performance and practices in relation to environmental sustainability, social responsibility and corporate governance.

We utilised the B Corp and National Standards for Volunteer Involvement standard frameworks to form the criteria for which the ESG impact assessment would be evaluated against to assess NELA’s performance in FY2023.

A copy of the report can be found at: Sustainability Report 2023 – Final

Resources:

What is Sustainability?

What is the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Movement?

Who has a role in ESG & Sustainability?

References

1. What is Sustainability?

Sustainability is a ‘fuzzy’ concept that lacks an absolute definition and which may be interpreted and perceived variably.1

Sustainability is a normative concept (i.e. involving a value judgment) that seeks to represent something as ‘good’ or ‘better’ and beneficial for society as a whole.2

At its core, sustainability denotes a ‘measure of whether (or to what extent) a process or practice can continue’.3

This definition can then further refined to encompass ‘the capacity to maintain or improve the state and availability of desirable materials or conditions over the long term’.4

However, the most widely accepted contemporary definition of sustainability is ‘meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’, contained in the Brundtland Report entitled ‘Our Common Future’ by the World Commission on Environment and Development (or United Nations ‘Brundtland Commission’) in 1987.5

The pursuit of sustainability implies the goal of maintaining beneficial natural and social conditions (to sustain them) and, where practicable, improving on these conditions.

The breadth of sustainability

Sustainability is often associated with widely recognised issues such as climate change, loss of biodiversity, loss of ecosystem services, pollution or global warming that underpin notions of environmentalism.

However, sustainability is not just about environmentalism. It is an approach that requires holistic consideration as to how individuals, organisations and society operate in the ecological, social and economic environment.6

Contemporary approaches to sustainability generally make reference to the ‘three pillars’ of sustainability that provide a framework for understanding and addressing sustainability issues:

- Environment (or planet): includes matters such as the maintenance of ecological integrity by consideration of areas such as water quality, air quality, greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity..

- Social (or people): includes matters such as poverty, social justice, peace, security, equality, quality of living, access to healthcare and education, culture, heritage and religion.

- Economic (or profit): includes matters such as economic growth, wealth inequity, job creation, production, distribution, consumption, growth and employment.

The three pillars are fundamental to many companies, organisations, institutions, government bodies, non-governmental organisations and international organisations by interacting harmoniously to achieving sustainable development in pursuit of the betterment of our planet.

Achieving global sustainability

The need for a sustainability transition is not a novel issue; it remains an urgent priority on a global scale.7

The prevalence of the ongoing ecological and social crises, as well as heightened public awareness of such crises, continues to serve as the impetus for change, with increasing pressures on companies, governments, and other organisations to work towards the ‘systemic adoption of markedly better environmental and social practices’.8

There is a paramount need to set real and tangible goals that can be accurately and transparently tracked to promote best sustainability practices to facilitate the transition towards a sustainable world.

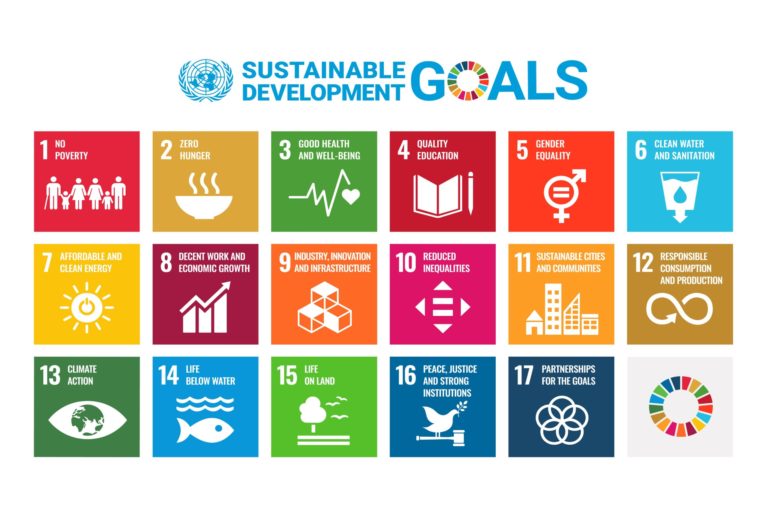

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals and United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) illustrates a global effort aimed at creating a better, fairer and more sustainable world by 2030 by addressing global challenges to sustainability.

The aim is underpinned by the three pillars of sustainability that set out a plan of action for socially and environmentally sound economic development through 17 SDGS.

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs: Sustainable Development (2023)

2.What is the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Movement?

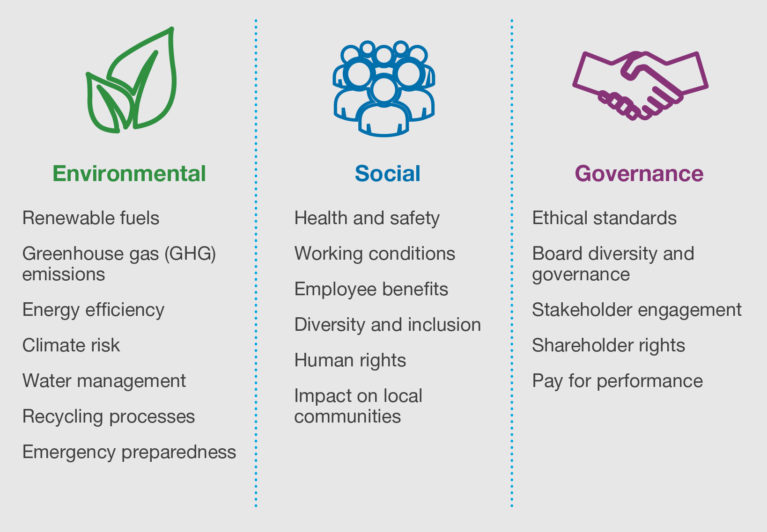

ESG provides a framework of integrated reporting through which impact on environmental, social, and governance concerns can be evaluated.

The ESG movement represents a paradigm shift away from traditional understandings of the success of a business or activity: from a sole focus on maximising profits for shareholders, or achieving a single goal, to a consideration of a broader array of stakeholders including customers, employees, and society at large.9 The movement is guided by the principle that transparency is the key to accountability on impacts. ESG frameworks have increasingly been used as a powerful governance and baseline tool to guide decision-making regarding investment strategies by large institutional investors such as pensions and mutual funds and sustainability improvements.

Source: World Economic Forum

Origins of ESG

The concept of ESG entered the mainstream debate with the publication of the first Who Cares Wins report by the UN Global Compact in 2004, which developed guidelines and recommendations on how to better integrate ESG issues in asset management, securities brokerage services and associated research functions.10The report made 25 recommendations targeted to stakeholders in the corporate and financial sectors including: financial analysts, financial institutions, companies, investors, trustees of pension funds, consultants and financial advisers, regulators, stock exchanges, and non-government organisations.

The relationship between ESG factors and financial performance

A meta-analysis of over 1000 individual studies into ESG from the NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business drew 6 conclusions from the research on the relationship between ESG and financial performance:11

- Improved financial performance due to ESG becomes more marked over time.

- When considering the success of different ESG investment strategies, ESG integration (where material ESG factors are integrated into investment analysis) was found to perform better than negative screening (where certain sectors or industries are entirely excluded from the investable universe.

- ESG investing appears to provide downside protection, especially during social or economic crisis.

- Sustainability initiatives at corporations appear to drive financial performance due to factors such as improved risk management and more innovation.

- Studies indicate that managing for a low carbon future improves financial performance.

- ESG disclosure on its own, i.e. without an accompanying strategy, does not drive financial performance.

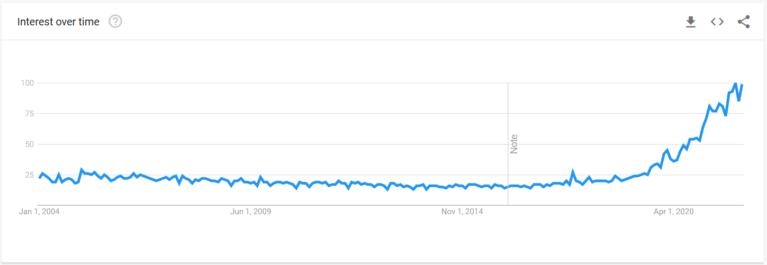

ESG in the public eye

Against heightened public awareness of the impacts of business on the environment and society, the rise of ESG-related litigation, and publication of greater guidance by regulators, interest in ESG has experienced a steady increase and will likely remain a key consideration in business and investment decision-making.

Google search term hits, ‘ESG’. Source: Google Trends

3. Who has a role in ESG & Sustainability?

Three key categories of contributors emerge as being crucial implementors of sustainability and arbitrators of whether successful sustainability has been achieved:

- Governments;

- Corporations; and

- Society – often represented by media, and Non-Government Organisations (“NGOs”).

We use the term contributors, as the strength of each, is not alone, but when they work together: ‘only a coordinated global effort, with participation from public, private and non government organisations, can achieve genuine systemic change”.12

Governments

The role of Government should be to ’order the behavior of individuals and organizations so economic and social policies are converted into outcomes’.13Government’s role and how they achieve this is through the:

- the legislative power to make the laws;

- the executive power to carry out and enforce the laws; and

- the judicial power to interpret laws and to judge whether they apply in individual cases.

. Governments exhibiting best practice in ESG and sustainability lead by example through strong internal impact awareness and disclosure, and incentivise transition costs for ESG risks and sustainability improvements.

If we accept that the role of law is to reflect society’s current norms and customs, there is a gap in how it is being enacted, as to whether it crafted to meet societies future needs.

The legal system in Australia focuses on governing the present, rather than on building a future Australia and promoting intergenerational equity. Key legislative means in Australia’s current system include for example, Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (WA), Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), and Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

Some progress has been made on shifting through reporting and reduction mechanisms for example, National Environment Protection (National Pollutant Inventory) Measure 1998 or National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (Safeguard Mechanism Rule), which is under current reform, but it falls short of achieving an intergenerational equity goal.

Currently Australian laws governing transparency in ESG reporting and setting sustainability targets do not have strong enforcement tools, leaving them to leverage reputation risk as a key mechanism for compliance.Whilst we acknowledge there will always be a legal form debate, as to whether hard or soft law is required, NELA support that a clear-eyed approach to the limitations of our current system, and ‘a revival of effective externality regulations’ is imperative’.14 Many laws which were designed with a singular intent for example, protecting the environment could improve sustainability outcomes and transparency of reporting through reform by linking compliance with ESG disclosures and sustainability improvements through target setting.

Corporations

Whether a corporation should have a social purpose is a hotly debated corporate governance question, with different international approaches. However, ‘a consensus is emerging that society and diversified investors are best served by companies that focus on value creation and respect the legitimate interests of all stakeholders, not just [shareholders]’.15

At the heart of this, is whether corporations can, and should be concerned with the interests of all stakeholders, being ‘any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives’,16 or shareholders only.

At the time of the 2004 Who Cares Wins reports at the UN Global Compact, the decision of Cowan v Scargill [1985] Ch 270 supported that portfolio managers could only take into account profit maximisation in order to fulfil their fiduciary duties. Following a review of the law across multiple jurisdictions including Australia, the UK, Canada, and the US, the authors found that integrating ESG considerations into an investment analysis in order to more reliably predict financial performance was legally permissible – in some jurisdictions, even required.17

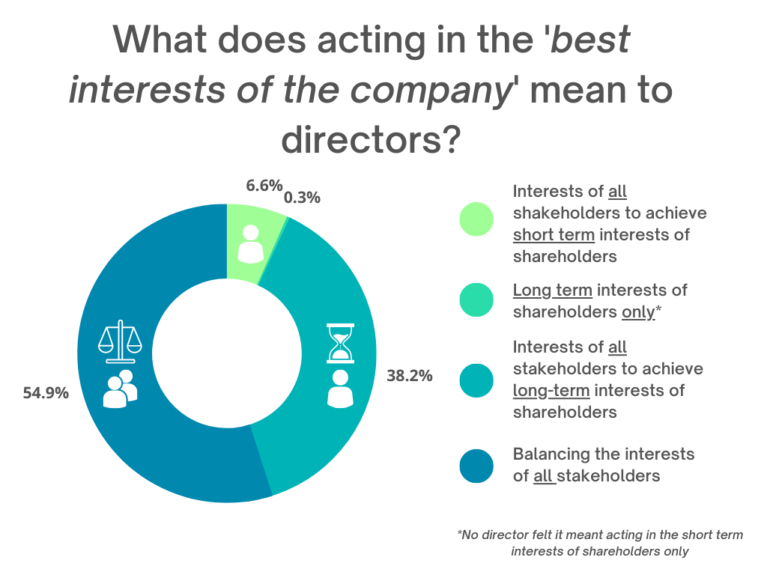

In Australia, Directors and Corporate Officers are obliged to discharge their duties ‘in good faith in the best interests of the corporation’.18There has been no direct judicial consideration of how to interpret this, however inquiries into corporate governance has shown that the law is ‘sufficiently permissive for directors to take into account non-shareholder interests’.19 The felt experience of Australian directors demonstrates that whilst a director’s decision-making motivation between stakeholder and shareholder primacy might be mixed, they do overwhelming feel that the interests of non-shareholders must be taken into account.20

NELA Original Graphic. Data Source: ‘Stakeholders and Director’s Duties Law, Theory, and Evidence’

Corporations are leading the way in ESG transparency and sustainability goal setting. With minimal legislative imperative, the drivers for are strongly based in a reflection of broader society desires, with customers enforcing their own required (see London Metal’s Exchange Responsible Sourcing Requirements)21and corporations proactively developing their own industry based standards (see International Council of Mining and Metals performance expectations.22

Society

Society has had, and will continue to have, a significant role to play in holding corporations and governments accountable for their sustainability and ESG commitments. For the purpose of this article, society is comprised of NGOs, citizen advocacy groups and individual citizens.

Why does society have an impact on sustainability and ESG outcomes?

Society influences corporate and governmental sustainability and ESG decisions through:

- Voting: for example,the 2022 federal election was colloquially referred to as the ‘climate election’. Climate change was one of the top concerns of voters. Candidates with strong positions on climate action were rewarded with votes.23 -In particular, voters in electorates that were impacted by climate-driven disasters, such as the 2022 floods, favoured climate-conscious candidates. Shareholdings: for example, billionaire and CEO of Atlassian, Mike Cannon-Brookes, convinced shareholders to vote in four directors to the Board of energy company, AGL, who pledge to guide the company towards decarbonisation.24Consumer power – for example, the power to boycott and buycott (choosing to purchase from ethically-conscious companies). The Deloitte Millennial and Gen Z Survey found that 59 percent of global consumers will stop buying a brand if they do not trust the company.25Companies are becoming more conscious of gaining a ‘social licence to operate’, referring to building community trust and confidence in the company’s operations.

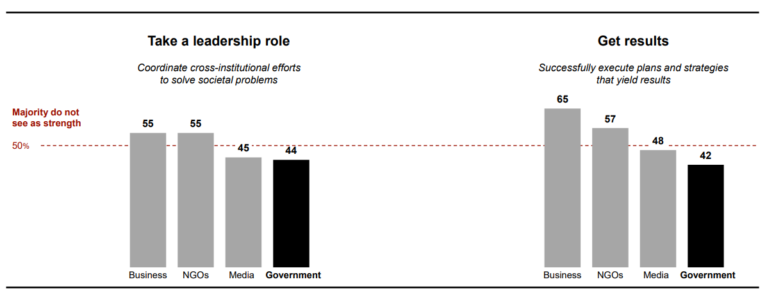

These are all depictions of trust, and trust is the ultimate currency in relationships. It is critical in working as co-contributors to achieving long-term sustainability. Our society does not have strong trust in governments, corporations, and even their own representatives (media and NGOs). Are not being seen as able to solve systemic societal problems:

Source: Edelman Trust, Edelman Trust Barometer 2022

How is society having an impact?

One way society can influence corporate and governmental sustainability and ESG impacts is through citizen-based litigation. Australia is second only to the United States for the number of climate-related ESG cases, despite our significantly smaller population.26

In the recent Santos NA Barossa Pty Ltd v Tipakalippa [2022] FCAFC 193 decision, the Federal Courtheld that Santos was required to consult the Munupi Clan about the potential impact of the company’s project to sea country. The Munupi Clan are Traditional Owners in the Tiwi Islands. They claimed that Santos’ Barossa gas project threatened their ‘food sources, culture and way of life’.27 This decision has had significant implications for the Barossa project, halting operations and forcing Santos to re-consider their plans for the area.

The Minister for the Environment v Sharma [2022] FCAFC 35 case was led by a group of Australian children who were concerned about the proposed greenhouse gas emissions from the government approved extension to the Vickery Coal Mine, in New South Wales. Although the children were unsuccessful on appeal, the case has paved the way for similar arguments to be brought in the future.

NGOs, citizen advocacy groups and individuals are taking ownership of their power to influence corporate and governmental decisions that impact people and the planet. It is likely society will only increase its voice in the sustainability and ESG sphere in future years.

References

| 1. See Jason Palmer, Ian Cooper and Rita van der Vorst, ‘Mapping out fuzzy buzzwords – who sits where on sustainability and sustainable development’ (1997) 5 Sustainable Development 87-93. |

| 2. Lisa Harrington, ‘Sustainability Theory and Conceptual Considerations: A Review of Key Ideas for Sustainability, and the Rural Context’ (2016) 2(4) Papers in Applied Geography 365, 373 (“Harrington”). |

| 3. Paul B Thompson and Patricia E Norris, Sustainability – What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, 2021) 1. |

| 4. Harrington (n 2) 366. |

| 5. UN Secretary-General, Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Note by the Secretary-General, UN GAOR, 42nd sess, Provisional Agenda Item 83(3), UN Doc A/42/427 (4 August 1987) pt 2.1 54[1]. |

| 6. Georgia Makridou, ‘Why should business embrace sustainability? Lessons from the world’s most sustainable energy companies’ (Impact Paper No. 2021-33-EN, ESCP Research Institute of Management, 2021) 2. |

| 7. In 2018, humanity was measured as using nature 1.7 times faster than ecosystems can regenerate (otherwise using 1.7 Earths); in 2020, conservative estimates indicated demand for biological resources of all people exceeded the amount Earth’s ecosystems produced by at least 56%: David Lin, Leopold Wambersie and Mathis Wackernagel, Calculating Earth Overshoot Day 2020: Estimates Point to August 22nd (Global Footprint Network, 2020). |

| 8. Magali Delmas, Thomas Lyon and John Maxwell, ‘Understanding the Role of the Corporation in Sustainability Transitions’ (2019) 32(2) Organization & Environment 87-97. |

| 9. Andrew Droste, ‘ESG & Stakeholder Capitalism’ (April 2020, Bloomberg Law Practical Guidance). |

| 10. UN Global Compact Financial Sector Initiative, Who Cares Wins – Connecting Financial Markets to a Changing World (Report, June 2004). |

| 11. Tensie Whelan et al, ESG and Financial Performance: Uncovering the Relationship by Aggregating Evidence from 1,000 Plus Studies Published between 2015-2020 (NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business) 3. |

| 12. Joseph Fiksel, ‘Sustainability and resilience: toward a systems approach’ (2006) 2(2) Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 14-21. |

| 13. World Bank, Governance and the Law -World Development Report 2017 (World Bank, 2017) 83. |

| 14. Leo E. Strine, ‘The Dangers of Denial: The Need for a Clear-Eyed Understanding of the Power and Accountability Structure Established by the Delaware General Corporation Law’ (Research Paper No. 15-08, Institute for Law and Economics, University of Pennsylvania Law School, 2015) 40. |

| 15. 3 Ways to Put Your Corporate Purpose into Action’ Harvard Business Review (Web Page, 13 March 2020). |

| 16. Robert Edward Freeman, Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach (Pitman, 1984) 53. |

| 17. Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, A legal framework for the integration of environmental, social and governance issues into institutional investment (Report, October 2005) 13. |

| 18. Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 181(1). |

| 19. Shelley Marshall and Ian Ramsay, ’Stakeholders and Director’s Duties Law, Theory and Evidence’ (2012) 35(1) University of New South Wales Law Journal 300; and Tony Feathersone, Shareholder versus stakeholder capitalism, Australian Institute of Company Directors. |

| 20. Ibid (Marshall) 305-12. |

| 21. London Metals Exchange, Responsible Sourcing. |

| 22. International Council of Mining and Metals, Mining Principles: Performance Expectations. |

| 23. Climate Council, Climate Election 2022: Unpacking How Climate Concerned Australians Voted . |

| 24. Angela Macdonald-Smith, Use your power: Cannon-Brookes rallies AGL shareholders, Australian Financial Review. |

| 25. Deloitte, 2021 Millennial & Gen Z Survey (2021) 10. |

| 26. Climate Council, ‘What is Climate Litigation and How Can Australians Take Action?. |

| 27. Environmental Defenders Officer, Tiwi-islands-barossa-gas-drilling-challenge . |